Racism Embedded in America's Transportation Infrastructure

Written on

Chapter 1: Racism in Infrastructure

The phrase “highways do not go in straight lines” holds significant meaning in the context of American infrastructure. Indeed, as Pete Buttigieg rightly pointed out, systemic racism is woven into the very fabric of how our transportation systems have been constructed. The development of highways has led to the devastation of numerous Black communities nationwide.

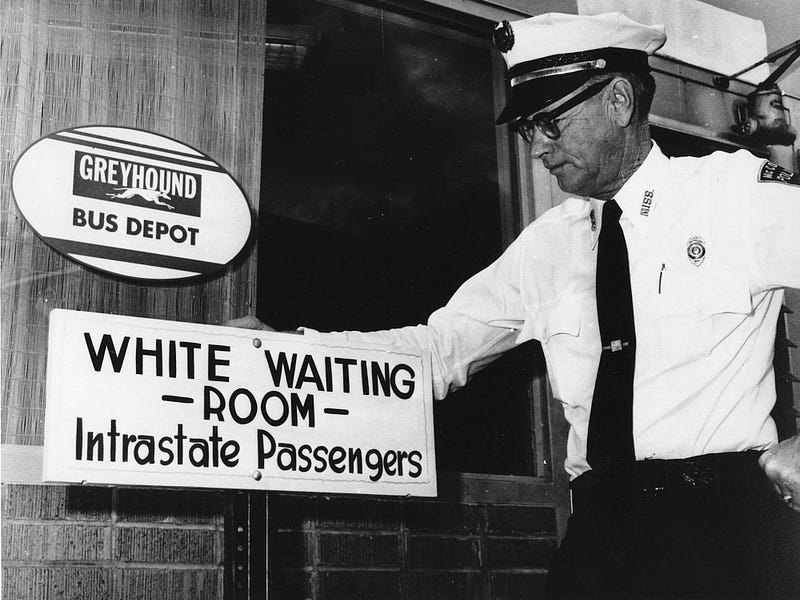

George H. Guy, a police chief, stands next to a sign indicating the “White waiting room” at the Greyhound bus station in McComb, MI, dated November 2, 1961. Photo: AP Photo

By Irene Jiang

Ora Lee Patterson recalls her upbringing in Rondo, a neighborhood in St. Paul, Minnesota, known for its thriving Black community. The area boasted a vibrant social scene and flourishing small businesses, resembling Harlem in many ways. However, the Federal Highway Act of 1956 permitted the state to confiscate extensive areas of homes and businesses through eminent domain, leading to the destruction of Rondo's central thoroughfare for the construction of Interstate 94, a massive 1,500-mile highway connecting the Great Lakes to the western states.

Patterson and her family were uprooted from their home, alongside numerous other Black families. Some residences were demolished, while others were relocated and sold elsewhere. The once-thriving neighborhood dwindled in vitality, becoming just one of many predominantly Black areas across the U.S. that were dismantled in the name of urban development during the mid-20th century. Communities such as Overtown in Miami, West Baltimore, and Milwaukee’s North Side faced similar fates.

The establishment of highways through predominantly Black and low-income neighborhoods stifled their growth and inflicted emotional distress on residents who lost their homes and communities. Buttigieg articulated this sentiment in an interview with The Grio, emphasizing that "racism is physically embedded in some of our highways."

Despite immediate backlash from conservative commentators, historical evidence supports Buttigieg's assertion, a viewpoint echoed by urban planning experts. Dr. Robert Bullard, a leading authority in environmental policy at Texas Southern University, remarked, “Highways do not follow straight paths for no reason.”

“Highways have obliterated numerous viable business districts in communities of color,” he elaborated, noting that highway construction often bypassed affluent white neighborhoods, directly impacting poorer areas. Bullard, recognized as the "father" of the environmental justice movement, urges critics of Buttigieg’s statements to educate themselves on the historical context. Currently, he contributes to the White House’s advisory council on environmental justice, striving to influence President Joe Biden’s policies regarding transportation and the environment.

“These are transformative times,” Bullard shared with Insider. “However, we cannot afford to wait another 40 years, as time is of the essence. All communities deserve the opportunity to thrive.”

Low-income Black neighborhoods were frequently victimized by the practice of redlining.

Many of the challenges faced by these communities can be traced back to mid-20th-century redlining practices, where the U.S. government classified neighborhoods by perceived investment risk based on residents’ race and income. Federal regulators primarily supported mortgages and subsidized housing in low-risk areas, typically affluent white neighborhoods, while designating low-income and Black neighborhoods as high-risk, often for explicitly racial reasons.

Mapping Inequality's interactive redlining map highlights terms such as “colored people,” “negroes,” and “foreigners” used by regulators to j