Exploring the Future: Humanity's Quest to Save Earth from the Sun

Written on

Chapter 1: The Dangers of an Aging Sun

As we look to the future, concerns about the sun's increasing luminosity loom large. In approximately one billion years, the sun's brightness will rise by 10%, potentially triggering a runaway greenhouse effect that could turn Earth into a scorched wasteland, reminiscent of Venus. The situation will worsen in about five billion years when the sun reaches its Schönberg–Chandrasekhar limit and transforms into a red giant, possibly becoming up to 1,000 times brighter than it is today. At this stage, Earth risks being either incinerated or swallowed by the sun's expanding outer layers.

Given our emotional attachment to the planet and our reliance on it for survival, humanity is determined to protect Earth. This notion was previously explored in my article "When Jupiter Becomes a Star," where we considered relocating Earth and converting Jupiter into a new energy source. Here, we will investigate an alternative solution: modifying the star itself.

The sun's inevitable evolution into a red giant poses a significant threat. However, what if we could extend its life significantly, granting us more time to thrive in its orbit?

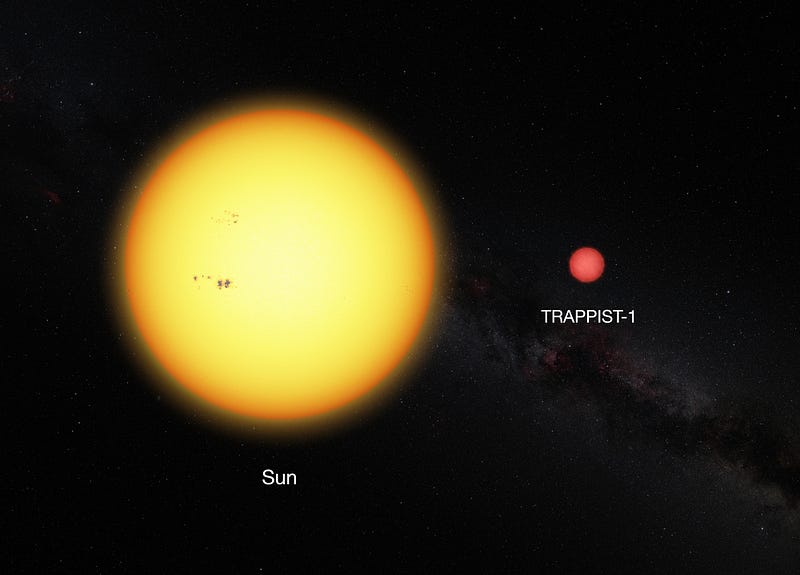

Both a star's luminosity and lifespan are closely linked to its mass. Typically, stars with lower mass can sustain their main sequence for longer periods—an example being a star with half the sun's mass, which can maintain its stable phase for four to eight times longer. This would provide us with tens of billions of extra years before transitioning into a voracious red giant. Could we, therefore, decrease our sun's mass to prolong its existence?

The concept of "Star Lifting," introduced by David Criswell from the California Space Institute, explores this idea. Star Lifting involves removing mass from stars. In a method he coined the "Huff-n-Puff" technique, a series of ion accelerators would orbit the sun, generating two counter-directed beams of oppositely charged ions. This would create a magnetic field allowing plasma to escape through two polar holes. By heating the sun's upper atmosphere with solar-powered lasers and particle beams, we could expel solar mass through these magnetic openings, effectively reducing the sun's overall mass. If we could utilize just 10% of the sun's energy for this purpose, we might achieve a stellar mass reduction of around 0.1% annually.

Criswell's ambition is to lower the sun's mass to 8% of its original size, enabling it to continue burning hydrogen while transforming it into a dim red dwarf star that could last an astonishing 23,000 billion years—over 1,000 times the current age of the universe. Furthermore, the mass that is lifted could be repurposed to create smaller, long-lasting stars, thereby supplying energy to Earth for eons.

Imagine a solar system where the planets orbit not one, but twelve small red dwarf stars, each capable of sustaining solar energy for billions of years.

Of course, astroengineering solutions are rarely straightforward.

Chapter 2: The Paradox of Mass Removal

Interestingly, both adding and removing mass can hasten the aging process of stars. Removing mass lowers the overall mass of a star while increasing the core-to-star mass ratio. This alteration can trick the star into behaving as if it is older than it truly is. For instance, if we were to remove 92% of the sun's mass, we would be left with just the core, which would ultimately evolve into a white dwarf rather than the red dwarf we intended.

The task of reducing the sun's mass is fraught with risks. Should we inadvertently extract too much mass, we could exceed the Schönberg–Chandrasekhar limit, potentially triggering the very outcome we sought to avoid—a premature transition to a red giant.

Additionally, altering the sun's luminosity and mass would necessitate changes in Earth's orbit. Thus, we face the dual challenge of engineering both a star and our planet. Simulations of exoplanets indicate that stars with masses below 0.8 times that of the sun have habitable zones so close that the planets become tidally locked, leading to one side perpetually facing the star.

A sun with only 8% of its original mass could theoretically support artificial habitats in space, but if we want it to sustain Earth, we would face drastic ecological changes.

Ultimately, neither modifying Earth nor the sun presents a viable salvation strategy. What if we took an even bolder step? What if we replaced the sun with an entirely different star? This audacious idea will be explored in my next article. Surprisingly, despite its ambitious nature, this concept may prove to be the least complex to implement.

The first video explores the intriguing idea that the Sun is not the center of our solar system, shedding light on the dynamics of celestial bodies.

The second video delves into the concept of seasons, explaining how they are influenced by the Earth's relationship with the sun.