A Comprehensive Look at Measles Outbreaks and Vaccination Trends

Written on

Chapter 1: Understanding the Current Measles Situation

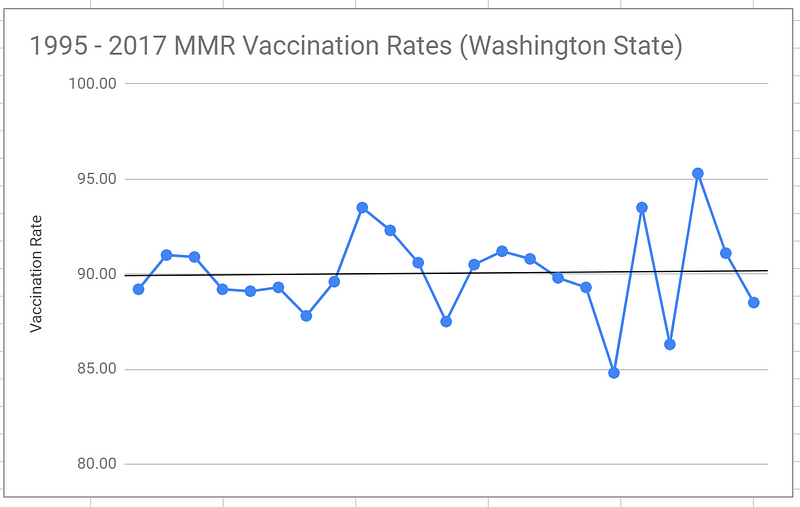

In a previous discussion regarding the measles outbreaks in the Pacific Northwest, I highlighted that vaccination rates have remained relatively unchanged since 1995. Here, I aim to delve deeper into that premise and evaluate specific assertions made by various sources.

Is the Washington Post's Claim Accurate?

Twitter has preserved a segment that seems to be absent from the actual article linked in Dr. Pan’s tweet, which states, "lax state laws have contributed to decreased vaccination rates across the Pacific Northwest." The article indicates the following:

The Pacific Northwest is a hotspot for organized anti-vaccination activists, which has resulted in low immunization rates for children in Washington, Oregon, and Idaho. In Idaho, as many as 10.5 percent of kindergartners are unvaccinated against measles, nearly double the national median rate.

So, is the article presenting the truth? I would categorize it as an “alternative fact.” Consider the following graphical data.

Washington State Vaccination Trends

In my earlier analysis, I examined immunization rates at both the regional and state levels. I now wish to provide further insight into Washington State’s vaccination statistics. Over the last few years, volatility in vaccination rates has increased, but it’s challenging to determine if this fluctuation is unusual. When individuals cite short-term data and claim a “decline” in vaccination rates, it’s akin to declaring "the Earth is cooling" based on a few cold winters. A thorough analysis must consider how these data points align with a broader dataset.

This graph depicts recent volatility. While the 2012 spike might be relevant, it doesn’t sufficiently account for the current outbreak timing since overall vaccination rates are averaged over several years, smoothing out year-to-year variations.

The Need for Improved Data

To draw more definitive conclusions, we require a significantly larger data set. It’s possible that changes may occur at the county level or even smaller units. If so, these shifts might not be captured in my current analysis. Yet, it doesn’t seem plausible that localized changes could significantly affect broader outbreaks. We can think of small communities as individual units within a larger population.

Interestingly, a recent surge in measles cases has led to a notable increase in vaccinations, as reported by Ars Technica. Therefore, we should expect to see rising vaccination rates in upcoming datasets, alongside a decrease in localized outbreaks.

Now, even if the source of recent outbreaks differs from anti-vaccine sentiments, we should observe a decline in cases because vaccines are effective in preventing symptoms. This fluctuation, however, may complicate data interpretation. A proper analysis must adjust for changes in vaccination rates when assessing whether the pathogen is becoming more virulent.

Asymptomatic Infection Insights

Given the recent outbreak and rapid shifts in vaccination rates among certain demographics, now is an opportune moment to investigate asymptomatic infections. As I discussed in my previous paper on whooping cough, asymptomatic infections remain poorly understood. Despite differences in the diseases and their vaccinations, we should find that infection rates are considerably lower among vaccinated individuals compared to unvaccinated ones. The extent of this difference could enhance our understanding of the measles vaccine's efficacy.

To shed light on potential findings, I encountered a study on measles vaccination in Taiwan, which was presented to me as supporting current measles vaccination knowledge. However, it appears that the basic reproduction rate does not fall below one based on random population sampling, indicating a challenge in achieving herd immunity. I am currently verifying with the authors whether this estimate assumes 100% vaccination.

The apparent “eradication” of measles in the U.S. contrasts with the medical consensus that a 95% vaccination rate should yield herd immunity, suggesting that asymptomatic infections may indeed be an issue. Consequently, a comprehensive analysis in the U.S. is essential.

Do Antivaxers Vaccinate?

Does it make sense for anti-vaccine sentiments to affect second and third doses while leaving initial doses of the MMR vaccine untouched? One counterargument to my initial analysis of measles vaccination practices in the U.S. is that the dataset does not differentiate how many doses were administered. It simply measures whether at least one dose was given. I previously assumed that while the data reflects the fraction of children receiving at least one dose, we could infer changes in vaccine hesitancy from these figures.

What justifies this assumption? Occam’s razor and the lack of alternative explanations for why an anti-vaxxer would opt for one dose while foregoing subsequent doses, particularly when later doses are administered after the age most children are diagnosed with autism.

The observation that rates for second and third doses tend to be lower than first doses does not undermine this argument. The reasoning remains that recent outbreaks stem from declining vaccination rates linked to anti-vaccine sentiments. Therefore, it is reasonable to expect that the percentage decrease in first-dose coverage mirrors the reductions in second and third doses.

Graphical Analysis Challenges

Another point I raised in discussions is the claim that while vaccination rates appear stable on a large scale, pockets of low vaccination exist. This assertion suggests that these pockets are highly localized. However, to substantiate this claim, we require community-level data to justify changes in vaccination patterns.

Moreover, if we analyze tightly-knit communities with low vaccination rates made up of familial and neighborhood units, we can view the population graph as a coarser representation, where each community acts as a single vertex.

The validity of this simplification hinges on whether these pockets are transient or persistent. If they are fleeting and frequently change, this approach is flawed. However, proponents argue these communities are stable, allowing for such simplification.

Using this model, we can assess the vaccination rates across these coarser graphs, reaffirming our previous observation of no significant changes in vaccination rates at that scale.

County-Level Data Availability

One counterpoint is the existence of county-level data. While we do possess some data for certain counties across years, a proper analysis requires comprehensive data from all counties within a state over several years. Merely pointing to one county with declining vaccination rates does not clarify the broader picture. We must consider whether decreases in one county correlate with increases in another. A thorough evaluation across all counties in a specific region over multiple years is vital to meaningfully interpret the data, as opposed to relying solely on anecdotal evidence.

Anti-Vax Clusters and Epidemic Dynamics

Another issue arises from the assertion that the anti-vaccine community is a close-knit group that frequently interacts. If true, the measles virus should be able to spread rapidly within such populations. When an infection occurs, individuals generally gain lasting immunity, leading to a scenario where the virus would circulate until only newborns remain susceptible. Ultimately, this would result in herd immunity within that community.

Non-Medical Exemptions (NMEs)

A further complication is the reliance on non-medical exemptions to gauge vaccination rates. Is this estimation valid? For instance, JoeWV posited that strict vaccine regulations in West Virginia shield the state from recent outbreaks, unlike Pennsylvania and Ohio, which have more lenient laws. However, West Virginia has consistently recorded lower vaccination rates than Pennsylvania, and Ohio's rates have often been comparable or slightly higher.

Therefore, we cannot solely depend on lax laws or NMEs to gauge actual vaccination behaviors.

The Shifting Burden of Proof

Lastly, I want to emphasize that I don’t bear the burden of proof in this discussion. While I am presenting extensive data on the topic, the responsibility lies with those making claims. The medical community has asserted that shifts in vaccination habits have led to recent outbreaks. Beyond the challenges of establishing causation, they must first substantiate the claim that vaccination behaviors have indeed changed. If they allege this change occurs at the county level, it is their duty to gather relevant data and conduct a thorough analysis. Until such evidence is presented, we are justified in questioning the assertion of causation.

This first video discusses the resurgence of measles in the U.S. and the FDA's approval of over-the-counter birth control pills, shedding light on the implications of these developments.

The second video provides a brief overview of the reasons behind the recent measles outbreaks, highlighting critical factors contributing to this public health issue.

Further Reading

Is the Anti-Vax Movement Being Used as a Scapegoat?

Vaccination is vital, yet the medical community may be too quick to attribute the recent measles outbreaks solely to the anti-vaccine movement.